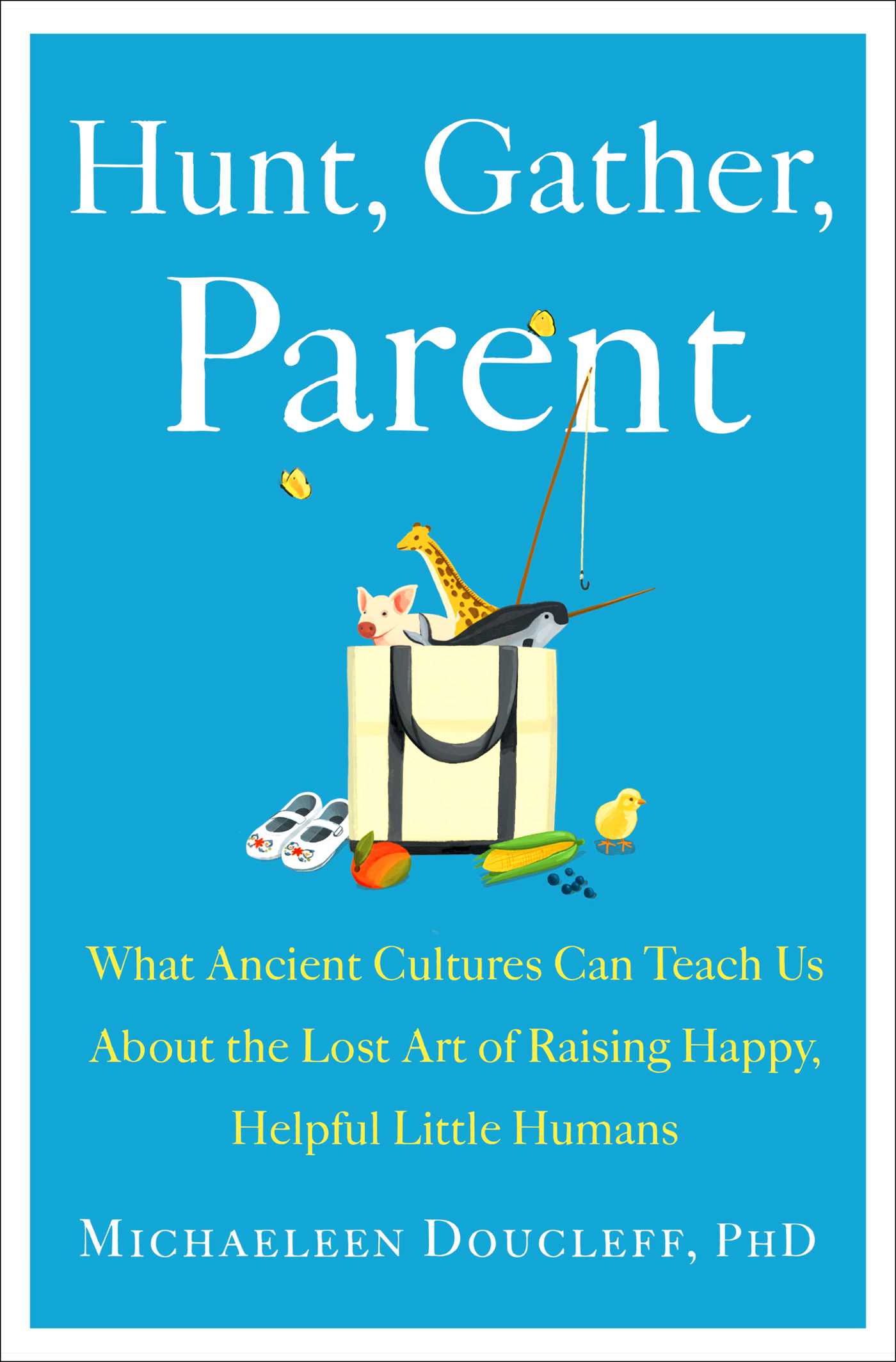

In Hunt, Gather, Parent: What Ancient Cultures Can Teach Us About the Lost Art of Raising Happy, Helpful Little Humans, Michaeleen Doucleff takes readers on a cross-cultural exploration of parenting. Combining journalism, anthropology, and personal reflection, Doucleff examines how ancient societies raise cooperative, confident, and emotionally grounded children without resorting to the control-based methods so common in Western homes.

After becoming a mother, Doucleff began questioning the effectiveness of modern parenting advice and sought alternatives rooted in real-world practice. Her journey takes her from the Maya villages of Mexico to the Arctic home of the Inuit, and finally to Tanzania with the Hadzabe. In each community, she discovers a radically different parenting paradigm one built on trust, inclusion, and emotional calm rather than fear, bribes, or timeouts.

Doucleff observes that Maya parents teach cooperation by involving children in household chores from a very young age. Inuit families nurture emotional intelligence through gentle storytelling and restraint, modeling calm even in moments of chaos. The Hadzabe, meanwhile, allow children to explore freely, cultivating independence and confidence. What unites these cultures, she argues, is their quiet understanding that children learn best by observing, participating, and belonging.

Where the book shines is in its practicality. Doucleff translates her discoveries into actionable insights that any parent can try immediately. She offers concrete ways to invite children into cooperation rather than confrontation, to discipline without yelling, and to replace rigid rules with empathy and partnership. Readers like Phillip have praised these sections for being filled with real examples and “action items” that feel genuinely useful.

However, the book is far from perfect. Many reviewers point out that its title overpromises a universal parenting theory when the material often reads more like a personal memoir. Doucleff’s sweeping use of the term “Western parenting” feels overly simplistic, and her narrative sometimes romanticizes Indigenous cultures in ways that flatten their complexities. Adria, another thoughtful reviewer, goes further questioning why publishers continue to prioritize Western authors interpreting Indigenous wisdom instead of publishing the voices of those parents themselves.

There is also a noticeable gender gap in Doucleff’s storytelling. Fathers and sons are almost invisible until late in the book, leaving readers especially dads wondering where their experiences fit into this “universal” parenting model. The absence of commentary on male roles in child-rearing undermines what could have been a more inclusive exploration of family dynamics.

Other readers, like C, find Doucleff’s tone at times grating and her first-person narrative self-centered. The frequent anecdotes about her daughter, Rosie, make the book feel narrow in scope. As C points out, Doucleff’s conclusions might apply well to her own household but fail to account for working-class families or parents raising multiple children. The book’s power diminishes whenever it shifts away from anthropology and toward personal confession.

Still, Hunt, Gather, Parent offers a refreshing antidote to the stress of modern child-rearing. Its central message that cooperation, trust, and emotional calm can replace control, fear, and exhaustion is one worth taking to heart. Doucleff’s work may not be flawless, but it opens an important conversation about what parenting could look like if we learned from, rather than looked down on, ancient wisdom.

If you are searching for a parenting guide that blends science, storytelling, and cross-cultural insight, Hunt, Gather, Parent is worth your attention. It may not have all the answers, but it will make you question the ones you thought you already had.