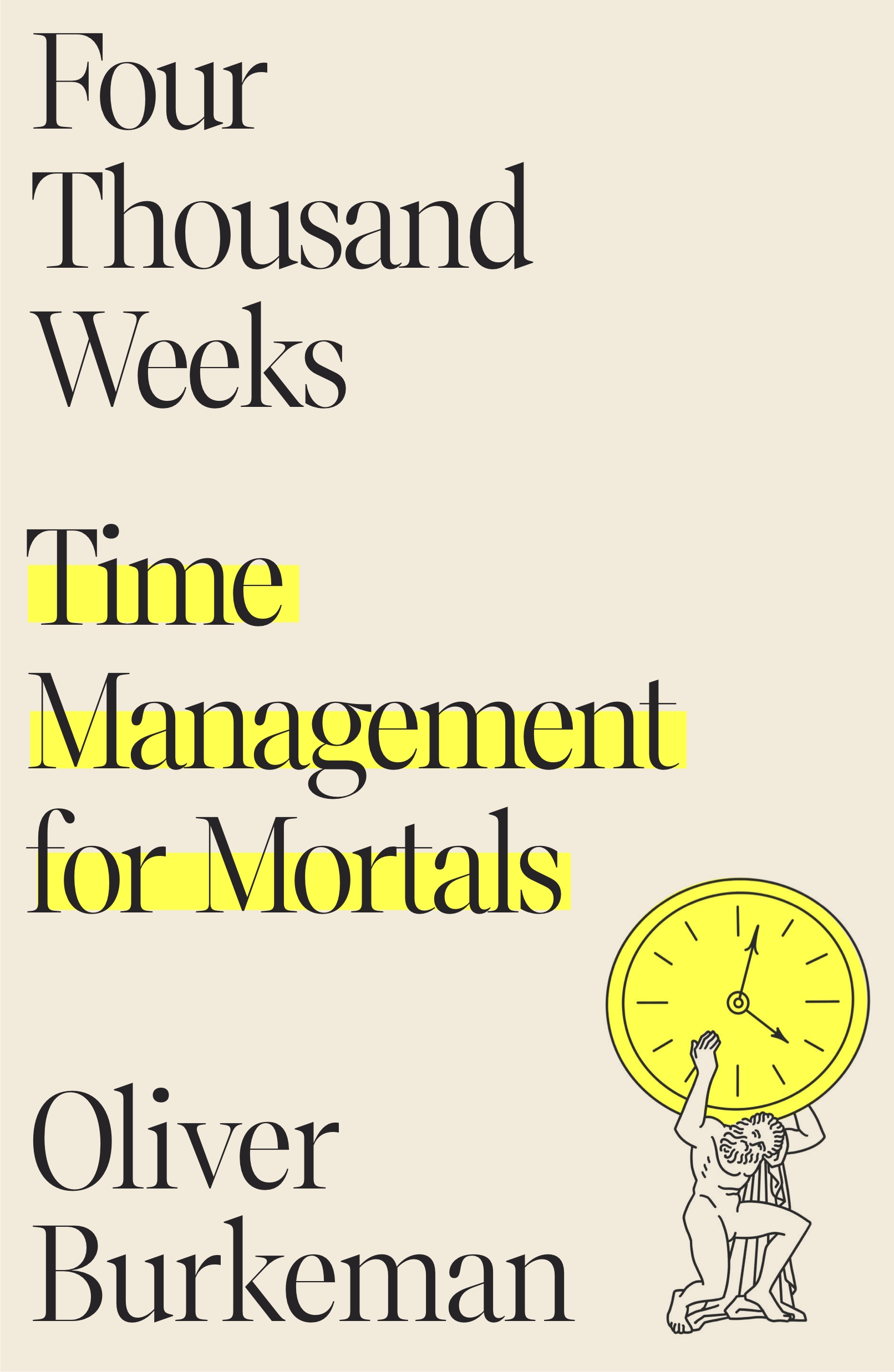

What if everything you’ve been told about time management is wrong? That’s the provocative question at the heart of Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, a book that doesn’t teach you how to squeeze more into your schedule, but instead asks you to confront the uncomfortable truth about the brevity of life.

If you live to be eighty, you will have just over four thousand weeks on this planet. That number alone is enough to jolt you into awareness, but Burkeman doesn’t stop there. Drawing from ancient philosophy, psychology, and spirituality, he offers an entirely different lens on productivity one that focuses less on doing more and more on finding meaning in what we choose to do.

This is not a typical self-help book filled with hacks and techniques to optimize your day. As reviewer Ryan Boissonneault aptly pointed out, “Rather than offering cheap time hacks to get more of the same bullshit done, this more philosophical work is based on two important but uncomfortable truths: you’ll never accomplish everything you want, and even if you could, it wouldn’t matter in the end.” Instead of teaching you how to manage your time better, Burkeman teaches you how to accept that you cannot manage it all. And oddly enough, that acceptance can be freeing.

Misha, who listened to the audiobook version narrated by the author, summarized it best through the five reflective questions Burkeman poses. They challenge readers to choose “uncomfortable enlargement over comfortable diminishment,” to drop impossible standards, to stop waiting until they “feel ready,” and to act generously and curiously in the present moment. These ideas form the emotional and philosophical core of the book.

But Burkeman doesn’t just leave readers in existential freefall. In his appendix, he provides ten practical tools for embracing finitude. Among them: keep a fixed-volume approach to productivity (limit how much you take on), serialize your projects (finish one before starting another), decide in advance what to fail at, and cultivate instantaneous generosity. He even advocates for “boring technology” like reading on a Kindle instead of scrolling your phone to reclaim your attention. Each tip, though simple, echoes a deeper message: time is not a resource to dominate, but a reality to live within.

Lisa O offered a more critical take, noting that Four Thousand Weeks feels “like a personal journaling exercise,” oscillating between optimism and despair. She’s right that the book can feel repetitive and introspective, especially if you’re not someone plagued by time anxiety. Burkeman’s voice is more contemplative than instructive, often circling back to the same realization: life is finite, and the only way to find peace is to stop pretending otherwise. Yet for readers who’ve spent years chasing productivity systems or feeling crushed by endless to-do lists, that repetition might feel more like reassurance than redundancy.

Ultimately, Four Thousand Weeks is less a time management manual and more a meditation on what it means to be human in a culture obsessed with busyness. It invites you to stop treating life as a problem to be solved and instead see it as something to be experienced, imperfectly and fully.

It is not a book for everyone. But for those who are ready to step off the treadmill of endless striving and confront the fleeting nature of existence, Burkeman’s words may be nothing short of life-changing.

I give Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals 4.5 out of 5 stars.

If you’re ready to rethink your relationship with time, you can get your copy here: Buy on Amazon.