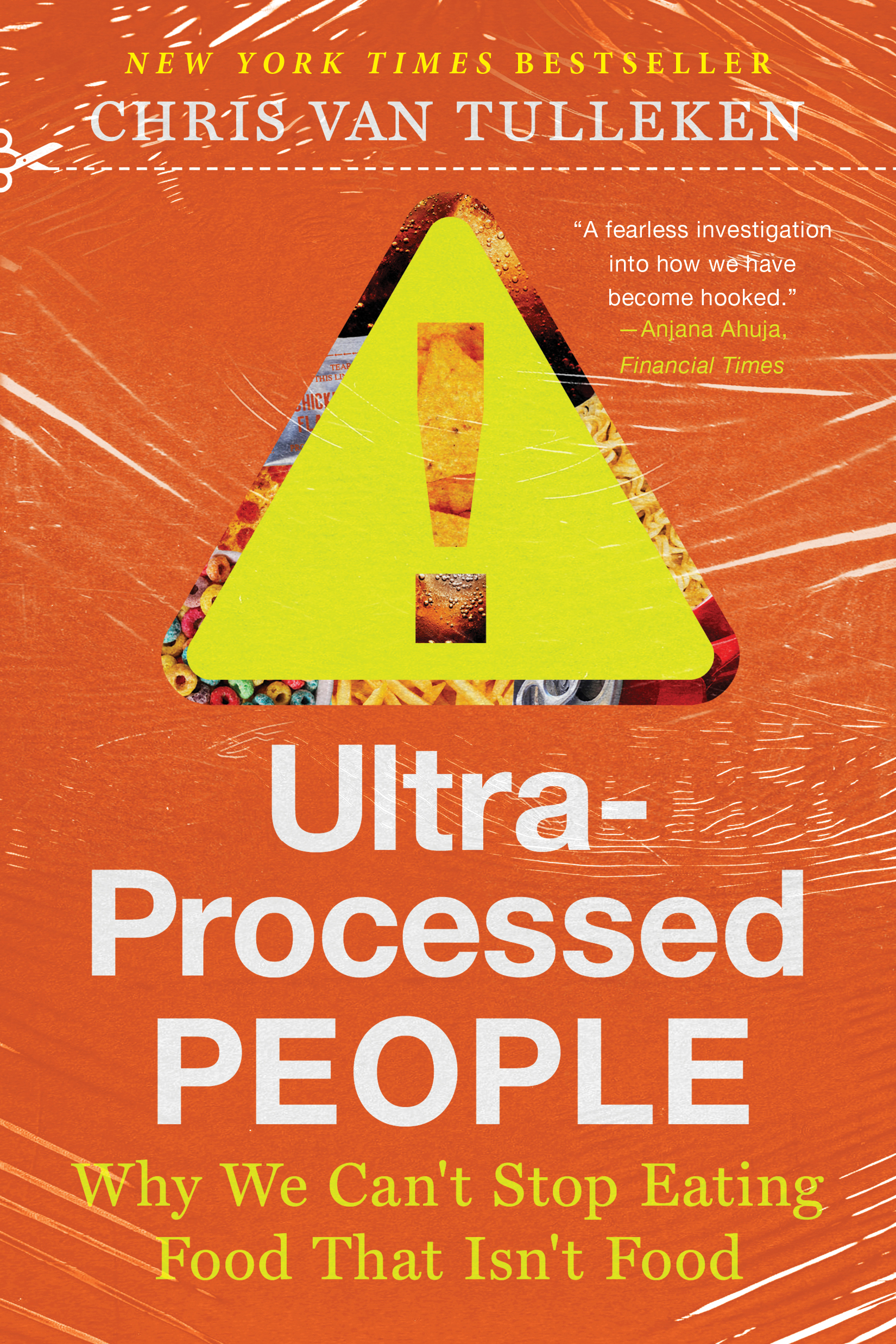

Chris van Tulleken’s Ultra-Processed People is the rare health book that reads like a thriller and stings like a manifesto. It asks a deceptively simple question that reshapes everything that follows: what if much of what we eat is not really food at all, but an industrial product designed to keep us hungry, hooked, and coming back for more?

What counts as UPF and why it matters

Van Tulleken cuts through jargon with a practical rule of thumb: if it comes wrapped in plastic and includes an ingredient you would not stock in a home kitchen, it likely counts as ultra-processed food. Think emulsifiers like xanthan gum or mono- and diglycerides, stabilizers, artificial sweeteners, engineered flavors, and protein isolates. The point is not to panic about one mysterious ingredient. It is to recognize a pattern of formulation that prioritizes shelf life, mouthfeel, and “moreishness” over nourishment.

The most unsettling takeaway is that UPF is not a fringe problem. It is the default diet in many wealthy countries and increasingly the only affordable option in many neighborhoods. That reality makes this a story about health, but also about economics, regulation, and access.

The self-experiment that hooks you

To test the hypothesis, van Tulleken eats a diet that is 80 percent UPF for a month under medical supervision. He documents rapid weight gain, changes in hunger and satiety hormones, and even differences visible on a brain scan related to reward pathways. He pairs this with a broad tour of the science on palatability engineering, hyper-availability of calories, and the way UPF appears to drive excess intake beyond what its fat and sugar content alone would predict.

This section is the book’s beating heart. It is gripping because it is personal, but it also serves a larger point: when the food system is engineered to keep us eating, telling people to rely on willpower is a bit like handing out umbrellas in a hurricane and calling it disaster response.

The evidence, strengths, and fair caveats

Van Tulleken is at his best when he shows how industry incentives align with biology. Companies optimize formulations through consumer panels and never ship the version that makes people eat less. He also highlights regulatory gaps, such as self-certification pathways for additives that let products move to market without much independent scrutiny.

Readers who want precision will appreciate that he does not hide the limits. Some findings come from correlation. Some mechanistic work relies on mice. Microbiome claims are promising but still evolving. A few readers may wish for tighter pacing in places or a more granular discussion of confounders. The author largely anticipates these objections, points to the highest quality studies available, and still makes a persuasive case that UPF is a significant driver of obesity and metabolic disease at the population level.

The psychology of eating what eats at us

One of the book’s sharpest insights is how UPF hijacks the brain’s reward system. Ultra-palatable combinations of refined starches, added fats, and engineered flavors can produce cue-driven eating that feels a lot like compulsion. That does not absolve personal agency, but it reframes the conversation. If an entire aisle is designed to defeat your stop signal, failure is not a character flaw. It is an expected outcome of the design.

Equity and the time cost of real food

Several reviewers’ reflections echo a hard truth that van Tulleken underscores. Moving away from UPF often requires more time, money, and kitchen access than many families can spare. It is easier to be virtuous about whole foods when you have the budget, the tools, the skills, and the schedule. The author does not scold readers for the realities of modern life. He repeatedly argues that meaningful change requires policy, not guilt. If governments subsidize ingredients for UPF while fresh food remains expensive or hard to reach, individual advice will never scale.

Will this actually change how you eat

Probably. The book does not offer a diet plan and it does not need one. Once you learn to scan a label for the telltale markers of industrial formulation, it becomes hard to unsee. Many readers report instantly rethinking their “sometimes treats” after confronting ingredient lists that read like a small chemistry set. Others keep some favorites but cut back overall. The goal is not purity. It is awareness and a shift toward food that looks like it did before a factory optimized it for speed, softness, and shelf life.

Final verdict

Ultra-Processed People is eye opening, occasionally infuriating, and deeply practical. It synthesizes science, lived experience, and industry context into a clear argument that the modern diet is not an accident. It is a business model. Van Tulleken shows why that model is bad for bodies and the planet, then offers a humane path forward that mixes household strategies with calls for structural reform.

If you want a page turner that could change your cart, this is it.